We test and review fitness products based on an independent, multi-point methodology. If you use our links to purchase something, we may earn a commission. Read our disclosures.

Key Takeaways

- Over 15 muscles in the body work together to perform a squat

- There are many different variations of squats such as front squats, back squats, split squats, goblet squats, etc.

- Squats primarily work your quads, hamstrings, and glutes

- Other muscles used during squats include your calves, adductors, lower and upper back, shoulders, and hip flexors

- Several muscles are supporting you during a squat such as core muscles, biceps, and forearms

- Squatting regularly has many benefits such as increased strength, mobility, flexibility, posture, balance, bone density, as well as increased hormone production

It doesn’t matter if you’re a bodybuilder, powerlifter, CrossFitter, or regular run-of-the-mill fitness enthusiast, the squat is one of the best compound exercises you could and should be doing in the gym. Period.

Whether you’re doing bodyweight squats or learning how to squat heavier, no other movement hits the lower body with such intensity. It’s one of the best all-around lifts for any fitness purposes, and provides benefits ranging from improved functional strength, better balance and stability, and bigger leg muscles.

There’s a lot happening during the squat on the physiological level, begging the question, “What muscles do squats work?” Beyond the no-brainer, primary movers of this omnipresent exercise, where else are we receiving muscle activation and assistance?

Today, we’re diving headfirst into the topic to uncover what muscles are working to complete the squat movement. We’ll also cover the innumerable benefits of squats and make recommendations for who should and perhaps should not be performing squats regularly.

Defining the Squat

Before we get started, what do we mean when we say “squat”? With so many variations and types of squats possible, what constitutes the squat anatomy for the purposes of our investigation?

Generally speaking, a squat is a compound exercise that involves hinging at the hips, bending at the knees, and lowering the body while keeping the back straight, chest up, and core tight. It’s considered to be one of the most effective exercises for building lower body strength, improving athletic performance, and promoting overall fitness.

Different types of squats include the bodyweight squat, barbell back squat, front squat, split squat, side squat, goblet squat–the list goes on. While most squat variations target the lower body muscles predominantly, the activation may increase or decrease depending on the variation used.

For the purposes of our article, we’re focusing on the barbell back squat, as this is ostensibly the most common squat type next to the humble bodyweight squat.

Back Squat: Muscles Worked

It’s no surprise that the back squat predominantly targets the lower body muscles, but what else receives activation from this all-encompassing compound exercise?

Primary Movers

The prime movers of the back squat include:

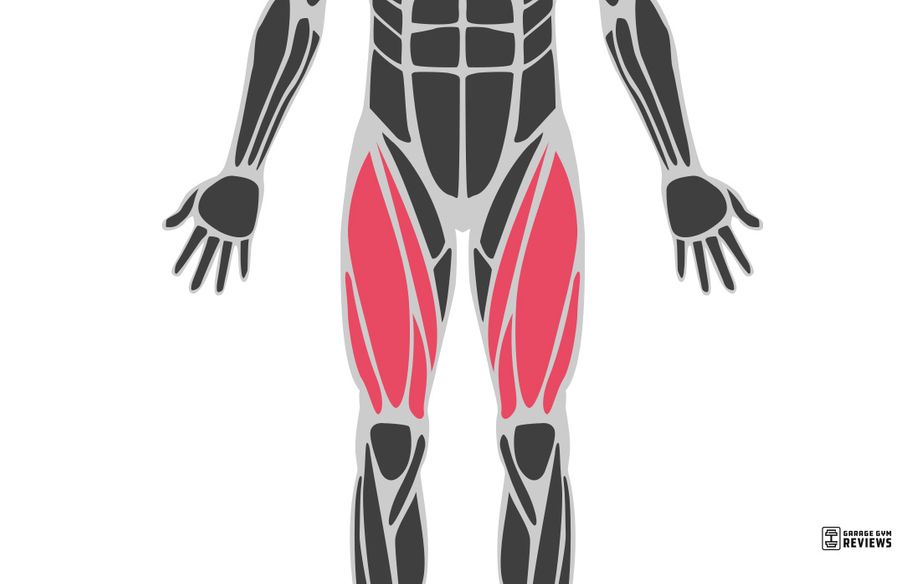

- Quadriceps: All four heads, the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius, receive activation during the back squat. This makes perfect sense, as your quads are responsible for knee flexion.

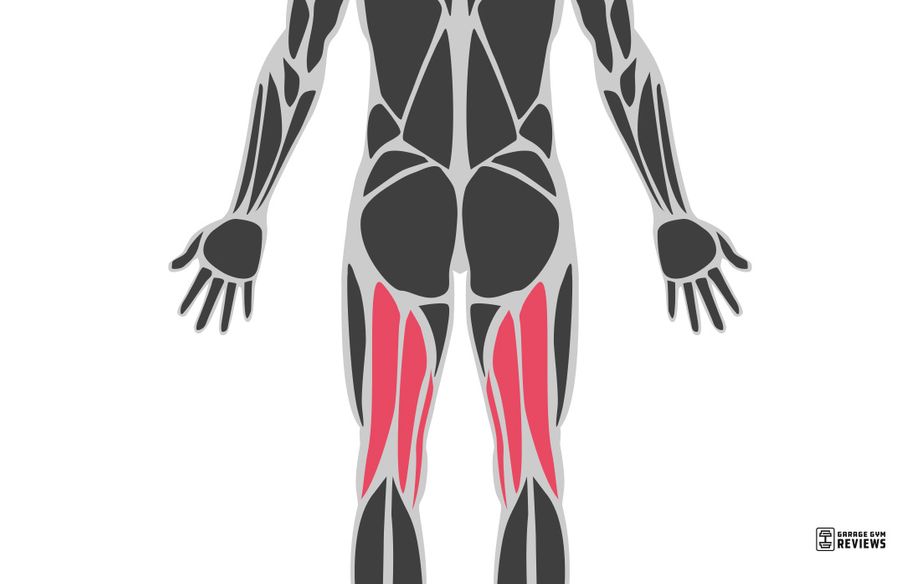

- Hamstrings: A squat is a great hamstring exercise because it works all parts; the two heads of the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus, play a vital role in completing the squat movement, specifically in assisting in the hip extension component of the movement.

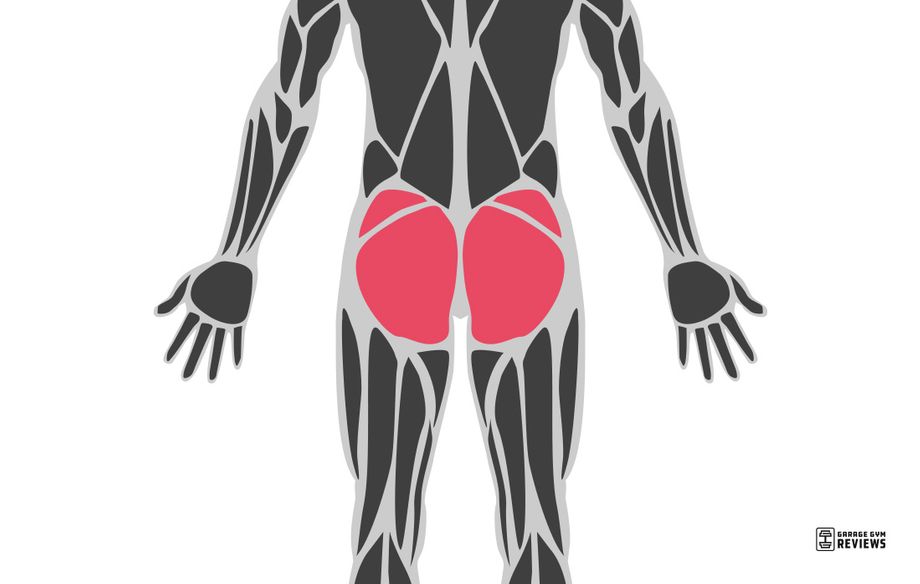

- Glutes: In addition to the hamstrings’ role in hip extension, your gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus all work to enable hip extension as well.

Of the primary movers, which muscles receive the most activation from the squat movement?

A 2012 review published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research1 used data from 18 different studies and determined that “hamstring and quadriceps activation was the higher than any other muscle group reported; biceps femoris and vastus medialis activation were each reported in 12 of the 18 studies.”

Of course, we feel the burn in our bums as well, especially after an unusually heavy set. The fact of the matter, however, is that you get the most activation in your quads and hamstrings.

RELATED: Proper Squat Form: Tips From An Olympian

Secondary Movers

Obviously, the lower body muscles enable the squat motion more so than other muscles, but what else plays a part in this classic functional exercise?

Secondary movers of the back squat include:

- Calves: The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles of the calves are also crucial during the squat movement. Since they’re responsible for plantar flexion of the ankle, you’ll need those calves during the upward phase of the back squat.

- Adductors: You need a strong drive from the heels to push the barbell back to the standing position during the squat, but you’ll also need excellent balance. You can thank the adductor muscles of your inner thighs for this, as they are used to stabilize your hips.

- Quadratus Lumborum: Located in the lower back, the quadratus lumborum muscles help to stabilize the pelvis and spine during the squat.

- Upper back and shoulder muscles: Just because squats are a key player on leg day doesn’t mean their benefits are exclusive to the lower body. To complete the squat movement, you’ll also need strong trapezius muscles, rhomboids, and deltoids to support the weight of the barbell and maintain a good, tall posture.

- Hip flexors: The hip flexor muscles, including the iliopsoas and rectus femoris, are important during the downward phase of the squat, helping you maintain hip and knee flexion.

Tertiary Movers or Supporting Muscles

Between primary and secondary movers alone, you’re hitting muscle groups from head to toe, but that’s not all. Did you know that the squat is actually one of the best ab exercises?

There are several tertiary movers and supporting muscles that help keep things tight during the squat movement, including:

- Rectus Abdominis: Also known as the “six-pack” muscle, the rectus abdominis in your core helps to stabilize your torso as you maintain a strong stance.

- Obliques: The abdominal muscles in the center of your upper body aren’t the only ones at work. You’ll also need strong oblique muscles to assist in maintaining proper form.

- Transverse Abdominis: The transverse abdominis, located deep in the abdominal wall, helps to provide stability and support to the core during the squat.

- Thoracic Erector Spinae: The erector spinae muscles of the thoracic spine, located in the upper back, helps stabilize the spine, prevent rounding of the back, and protect you from nasty injuries during the squat.

- Biceps: Believe it or not, the biceps get some activation, specifically from holding the heavy barbell on your back and shoulders during the squat movement.

- Forearms: In addition to the biceps, your forearms also assist in supporting the weight of the barbell and keeping it firmly in place as you descend down and drive back up during your squat sets.

The back squat is a complex movement that involves multiple muscle groups and requires a high degree of coordination and stability throughout the body. You’ll need a myriad of muscles along the kinetic chain to maintain proper form and derive the strength needed during barbell back squat reps.

While we mostly consider the back squat a leg exercise, it’s dismissive to think of it as just a leg exercise while so many other muscles are receiving activation.

Benefits of Squats

There are innumerable benefits of squats; here, we’ll dive into a few.

Increase Size and Strength

In regard to physical fitness, there are few strength-building squat rack exercises that provide a similar scope of muscle activation and, when it comes to lower body builders, the back squat reigns supreme.

Given the sheer magnitude of EMG-measured activation in the lower extremities, trunk, and other surrounding muscle groups, the back squat is ostensibly the best lower-body muscle builder bar none. Incorporating back squats and other squat variations into your workout routine should yield attractive gains in both muscle strength and size.

Support ADL

The squat movement is incredibly functional as well. Everyday activities, like sitting and lifting objects, utilize the same movement and employ the same muscles as used during the squat exercise. Strengthening the muscles used during the squat movement not only assists in ADL, or activities of daily living, but helps reduce a person’s risk of injury, both in and out of the gym.

Build Core Muscles

Squats are excellent for building core muscles. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Human Kinetics2 compared 6-RM back squats with the prone bridge, or plank. The study concluded that both the back squat and plank produce similar muscle activation in the abdominal muscles, specifically the rectus abdominis and the external obliques, but the squat provides “greater erector spinae activation,” making it the superior choice for building strong abs.

Boost Natural Hormone Production

Barbell squats also encourage the production of hormones like testosterone, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor and cortisol, which assist in post-workout hypertrophy and tissue repair. A 2018 randomized controlled trial published in Neuroendocrinology Letters3 concluded “squats [seem] to drive hormonal responses of GH, C and IGF-1, which may play a significant role in stimulating muscle growth and tissue regeneration.”

Improve Bone Density

Those looking to improve their bone density will benefit from resistance training exercises like the squat as well. A 2013 randomized controlled trial published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research4 stated that “squat exercise [maximal strength training] might serve as an effective intervention for patients with low bone mass,” and that squat training in this manner could serve “as a simple and effective training method for patients with reduced bone mass.”

From greater functional strength to building bulging quads, from enhancing hormone production to improving bone density, there are so many benefits associated with the back squat, it’s no wonder it’s one of the most popular leg exercises of all time.

Who Should Do Squats?

Short answer: everyone.

Unless you are medically contraindicated from performing the squat exercise, there are simply too many benefits to ignore. Everyday fitness enthusiasts, including those who participate in bodybuilding, powerlifting, and CrossFit, will benefit greatly from the improvements squats can provide regarding muscle size and strength.

Studies show that athletes will especially benefit from performing squats regularly.

A 2013 study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine5 sought “to determine the effects of body mass-based squat training on body composition, muscular strength and motor fitness in adolescent boys.”

The results indicated that “squat training for 8 weeks is a feasible and effective method for improving body composition and muscular strength of the knee extensors, and jump performance,” as vertical jump height saw a 3.4% improvement; an improvement which would be greatly beneficial in sports such as basketball, volleyball, and track and field.

That’s not all; a 2008 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research6 tested the sprinting speed of athletes after performing heavy sets of back squats and front squats. The study showed “significant increases in speed” observed in sprints performed after squatting, suggesting that “[incorporating heavy back squats] into the warm-up procedure of athletes to improve sprinting performance.”

RELATED: 10 Cross Training Exercises For Endurance Athletes

Older adults with diminished bone density could benefit from incorporating squats and other forms of resistance training into their workout regimen as well.

Who Shouldn’t Do Squats?

Most individuals will benefit from incorporating squats into their workout routine, but some folks might be better off steering clear.

A 2010 review published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research7 breaks down the kinematics of this common compound movement, detailing the role played by the ankle, the ACL, the hips, and the spine. The study warns that poor form places undue stress at these locations, especially when placed under an external load like a barbell, contributing to injury.

Those who have previously suffered a knee, hip, back, or ankle injury might need to take special precautions before squatting or refrain altogether for this reason.

Medical conditions like arthritis and osteoporosis could complicate one’s ability to squat as well. Some physicians and physical therapists might be apt to recommend squatting under certain conditions to encourage recovery, but some may warn against squatting altogether.

If you have previously suffered an injury or suffer from a medical condition that could preclude you from squatting, consult a medical professional before adding squats to your exercise regimen.

Final Thoughts: What Muscles Do Squats Work?

Squats are a leg day staple, so it’s only natural we call the squat a “leg exercise.” It’s not wrong to do so, but that only paints part of the picture.

In reality, the back squat is one of the most comprehensive compound movements available, employing muscles from groups all along the kinetic chain.

- The prime movers of the back squat include the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes.

- The secondary movers include the calves, adductors, quadratus lumborum, upper back and shoulder muscles, and hip flexors.

- The tertiary movers or supporting muscles include the rectus abdominis, obliques, traverse abdominis, thoracic erector spinae, biceps, and forearms.

Overall, squats target a heck of a lot of muscles from head to toe, and they provide ample benefits to those who squat regularly.

If you’re able to add squats into your routine, we couldn’t recommend them more highly.

FAQ: What Muscles Do Squats Work?

What muscles do squats work the most?

The muscles that receive the most activation during the squat exercise are the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes.

Squats work a multitude of other muscle groups from the upper back to the calves to the core, but you’ll receive the most activation in the leg muscles based on observed EMG activity.

What happens when you do squats everyday?

Squatting regularly offers benefits, including:

Improved strength and muscle mass

Increased mobility and flexibility

Improved posture and balance

Improved bone density

Increased production of T, GH, IGF-1, and cortisol

Squatting every day, on the other hand, poses some risks. Targeting the same muscle groups over and over without allowing enough time to properly recover puts you at risk for injury or overtraining. You might sneak by scot-free if you vary the type of squat or the intensity of the resistance (for example, hitting a heavy back squat on the first day and following it with bodyweight squats the next), but it’s generally advised to focus on another muscle group before squatting again.

Remember: You don’t make gains in the gym, you make them from recovering after going to the gym. Not taking enough time to recover only staggers your progress.

How many squats should you do a day?

The number of squats you should do in a day depends on your training goals. For example, if your goal is to squat more weight, you’ll want to do 1-3 squats at around 80-90% of your 1-rep max. For muscular endurance, you’ll want to do 10-15 reps at a much lighter weight.

Do squats tone belly fat?

Not directly, but if you brace properly while performing the squats you could strengthen your oblique muscles.

References

1. Clark DR, Lambert MI, Hunter AM. Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(4):1169-1178. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822d533d

2. van den Tillaar R, Saeterbakken AH. Comparison of Core Muscle Activation between a Prone Bridge and 6-RM Back Squats. J Hum Kinet. 2018;62:43-53. Published 2018 Jun 13. doi:10.1515/hukin-2017-0176

3. Wilk M, Petr M, Krzysztofik M, Zajac A, Stastny P. Endocrine response to high intensity barbell squats performed with constant movement tempo and variable training volume. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2018;39(4):342-348.

4. Mosti MP, Kaehler N, Stunes AK, Hoff J, Syversen U. Maximal strength training in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or osteopenia. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(10):2879-2886. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318280d4e2

5. Takai Y, Fukunaga Y, Fujita E, et al. Effects of body mass-based squat training in adolescent boys. J Sports Sci Med. 2013;12(1):60-65. Published 2013 Mar 1.

6. Yetter, Mike; Moir, Gavin L. The Acute Effects of Heavy Back and Front Squats on Speed during Forty-Meter Sprint Trials. J Strength Cond Res. 22(1):p 159-165, January 2008. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815f958d

7. Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(12):3497-3506. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac2d7

Further reading

Pump up your chest and add muscle and strength with our expert-vetted cable crossover exercise tips. Read more

Our team of certified personal trainers and nutrition coaches tested the best budget fitness trackers so you can track your daily health and wellness for less. Read more

Finding the best treadmill for your home gym can be tough. If you have limited space, the search becomes even more difficult, especially if you want a commercial-grade treadmill without all of the bulk. Enter: The ProForm Pro 9000 treadmill, a commercial-home-hybrid treadmill that doesn’t skimp on power. It even folds to create more floor space when you’re not using it.After testing more than a dozen treadmills from true commercial treadmills to budget treadmills, I’ve determined that the ProForm Pro 9000 is one of the top treadmills to get if you need one of the best cardio machines that stores with a relatively small footprint.My Favorite Things:22-inch HD display and quality graphicsBuilt-in workouts and handsfree incline/speed adjustmentsFoldable for easy storageMy Callouts:WiFi connectivity is mediocre at bestCustomer reviews complain of tech problemsQuality control seems inconsistent Read more

In this Sunny Health and Fitness SF-RW5801 Rowing Machine Review, I’ll tell you all the details you need to know about this budget-friendly rower to help you make a great purchasing decision. Read more